DETROIT — In 1989, while a postgraduate at Cranbrook Academy of Art, Nick Cave developed the first of his Soundsuits, for which he has become world-famous — sculptural bodysuits constructed from a range of found objects, which transform the wearer into a figure both highly visible and completely obscured. The Soundsuit was a means for Cave to process the intense vulnerability he felt as a black man during the Rodney King beating, which took place the same year he graduated with his MFA from Cranbrook, which boasts a lavish and sequestered campus in the affluent and mostly white Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills.

More than 25 years later, Laura Mott, curator of Contemporary Art and Design for the Cranbrook Art Museum, has collaborated with Cave to stage a monumental homecoming — a series of performances, installations, happenings, and publications collectively titled, Here Hear. In April, Cave began a series of Soundsuit photo shoots throughout Detroit, which are now in the form of an activity book at his astounding show which opened in June — Cave’s first solo show in Michigan. Here Hear features more than 30 of his Soundsuits, newly commissioned works, and selections from his last show at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York (Made by Whites for Whites). The show’s opening weekend was paired with a set of events in Detroit’s Brightmoor neighborhood — a long-forsaken region of the city, currently enjoying a fine art spotlight on the work that neighbors and community activists have been doing for decades to stabilize the area. Now, as July moves into August, a series of Dance Labs, facilitated by Cave, but developed and executed by creative communities within Detroit, are having their public debut.

The first took place on Sunday, July 18 at the Ruth Ellis Center, a facility dedicated exclusively to the support of LBGTQ runaway youth — the only of its kind in the city. A packed warehouse of people turned out to see the kids from Ruth Ellis dressed in costumes that Cave had dispatched in a box only a week earlier. Modern dancer and choreographer Biba Bell likewise only had a box of costumes and a week to work with another set of dancers to develop a performance for a crowd estimated between 800 and 1,000, at the Dequindre Cut — a biking/walking path installed along a former train track connecting the Detroit River Walk to the popular Easter Market district. The last of these Dance Labs will take place on Friday, July 31, at Campus Martius, dead center of the downtown business district. A final outdoor performance, “HeardDetroit,” will be held in late September, followed by the project’s culminating event, “Figure This: Detroit,” a recapping of all the performances at Detroit’s historic Masonic Temple. All these events are free and open to the public.

I was fortunate enough to get a moment with Cave, following a rehearsal out at Cranbrook, and we talked through some of the ins and outs of this ambitious year of events, the buzz about Detroit, and the fuel for his creative fire.

* * *

Sarah Rose Sharp: It strikes me that when someone’s coming to Detroit who hasn’t spent any time here and sees the performance at Artist Village, for example, they don’t see Brightmoor on a day-to-day basis, so it’s hard for them to understand what it means to have all these people show up suddenly. If you’re coming from somewhere like New York, and you see groups of people everywhere, you might not get what a big deal it is to really see people coming together like that.

Nick Cave: Yes. And also, what I think is interesting is, using the Brightmoor moment, is that they’re coming to and encountering Brightmoor. How does that resonate with you as a person, as a human being? There’s a lot of experiences along the way to a destination which are transformative. You can’t wear blinders and dismiss it. You have to pass through it to see it.

SRS: Right. By having an invitation or destination within that neighborhood, it opens up an opportunity to actually see the whole neighborhood as well.

NC: Exactly. As we’re doing the work, there are all of these things that I wasn’t necessarily aware of from a conscious point of view, until I was in the midst of it. With Brightmoor, and then the Village next door — just being able to create that kind of opportunity, for them to have all of these people present there, and how that sort of stimulates and brings revenue to the community.

SRS: Do you feel like being in Detroit, spending more time here, has informed the work that you’re doing right now? Or is it more about the work being generally informed by your experiences to date — sort of seeing how relevant it is in Detroit?

NC: My work, it’s really sort of what it’s doing to me, as an artist. It’s honing in and being sensitive to what’s important to me, and I’m interested in finding a larger purpose as a visual artist, more than what’s happening between museums and galleries. That really doesn’t provide me much. But you know, the civic work — where’s the purpose in the way that I’m interested in working? Where does that sit? What does that mean?

SRS: Right. I mean, galleries and museums are so interesting to me, because they are like a static field. You make this work, and it’s actually very much alive — I’m an artist, I handle things, I’m wearing things, or I’m touching things, I’m walking on them — and then people come into a gallery and suddenly no one can touch the art, and you’re sort of edging around it … It’s like seeing a tiger at a zoo and thinking that that’s where a tiger lives.

NC: Exactly. Exactly. There’s this sort of separation. Well, you know, I’m not interested in coming to Detroit and creating separations. I’m interested in coming to Detroit — providing you this opportunity [at Cranbrook] to be up close and personal with the work in this static format, but then also being able to get you into this performative experience. And working with the locals here to build it — it’s so multi-layered, in terms of what it takes. And we talk about how it takes a village to raise a child — well, it takes a village to create a creative encounter.

SRS: That’s interesting, too, because when I think about the kids at the Ruth Ellis Center, who did the first Dance Lab performance, I think it’s profound for a person who has worn one of your Soundsuits to be able to go to a museum and see one, and know that they were a part of that — what does it mean to really have a connection to that institution on a visceral, personal level?

NC: Exactly. And to be able to have a personal story that goes along with the understanding of that object. That’s an amazing opportunity. I mean, the kids that we were working with today for this performance had never been in a museum, period. This was the first time they’d ever been in a museum. So, how do we change the impulse of these places, these institutions, when still there are neighborhoods that don’t feel that they are welcome — they are, but not knowing that …

SRS: That it’s for them?

NC: That it’s for them. Exactly. And there’s still a lot of work that we can all do.

SRS: Yeah. I think moving things out into a context where people feel more comfortable and more at home is a great first step, because it’s understanding that these things [the Soundsuits] don’t just live in a museum — they can be found wandering your neighborhood. There’s this sense with the Soundsuits, when they enter a space, that they really electrify things. It’s like a creature; you don’t know what to do with it, and it opens this feeling that anything could happen. That’s something you maybe experience as a child, because you don’t know enough of the world to predict things yet —

NC: Right, I think that’s the thing with the work, it’s that we can’t really identify it. We tend to want to categorize things, we want to find its place in the world — but when you’re looking at something, and it’s something other, you really are not quite sure how to enter it. How is the form identified? Where does it come from? You’re trying to find that link to something familiar. And yet, it’s familiar from the perspective that it’s figurative, and then that becomes where the difficulty falls in — because there’s a sort of humanness to it, but yet it’s not of this world.

SRS: Right. It’s almost like seeing a yeti.

NC: Oh, yeah.

SRS: And it’s destabilizing, because you don’t really know how it’s going to move. How do I get out of its way? Trying to understand what the rules are.

NC: And then, you sort of try to identify — what is your position here? How do you stand up to this object? How do you come to it, without any sort of judgment? So I think there are a lot of things that we’re encountering — you can’t identify a gender, race, or class, so you’re just looking for that one thing.

SRS: A signifier, yes.

NC: And, as you’re saying, the unstableness of not being able to link it to anything. It’s really what I’m trying to do with the work. Or one of the things.

SRS: And it’s very empowering, right, to not be judged on your appearance? To have created a mechanism that allows you, or any wearer, to enter the space, but not be immediately pigeonholed by unchangeable aspects of who you are — it gives you a real kind of freedom to instill people with a different feeling than maybe you usually do, and what kind of an opportunity that is, on both sides.

I was really enchanted by the whole body of [non-Soundsuit] work in this gallery, because I’m familiar with the Soundsuits, but I love what you’re doing with objects, over here.

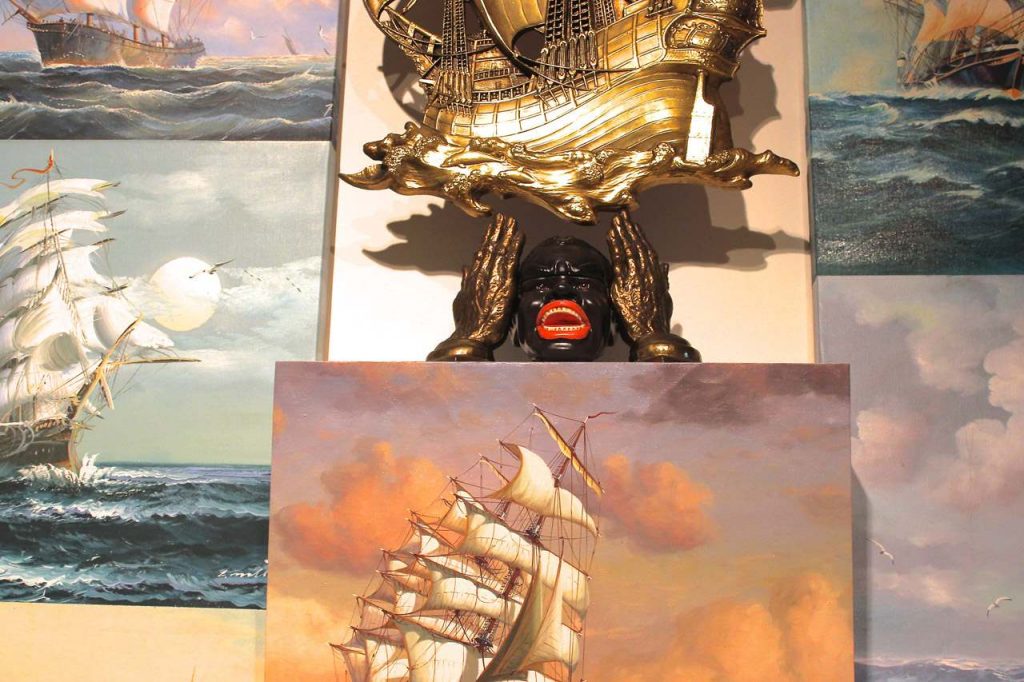

NC: Well, part of the exhibition is from my last solo show in New York, Made by Whites for Whites. And it really is me working backwards; it’s really what has always been behind the Soundsuits. It’s looking at a particular race, and really looking at the social commentary that’s happening in the world today — police brutality, profiling, black-on-black crime — it’s me dissecting the Soundsuit, and allowing this part to have a stronger presence in my body of work. I was also wanting to move away from the Soundsuits, and move into a different kind of format. I had been thinking about it, for probably three of four years, what does that mean, to transition into a different way of working, thinking, and making? And as I continued to work through that process, I realized that as long as I could transfer the essence, then I will be fine.

SRS: Do you seek these objects out on your own?

NC: Oh, yes. It’s the object that becomes the catalyst for me to proceed. How I go about looking for materials is that I jump on a plane, one-way ticket, and I’ll fly to Washington State, and I’ll rent a cargo van, and then I just pull out my phone and plug in antique malls as I’m traveling back to Illinois. So that’s how I go about scouting and looking for materials. I’m learning about the culture of the Northwest, versus Southeast, and just what are the differences, in terms of excess and surplus, that are going on there. It’s just so much stuff. And, you know, people think that I’m a hoarder, and I say I’m not, because what I need is really outside of my door. When I need it, I can go out and get it, because it’s just available, in that sense. So these are things that I’m looking for—but it’s never that I’m blinded by a particular mission. How do I keep myself very open to other things that perhaps may stimulate my mind to sort of perform, and to think about materials in a different way?

SRS: I like the aspect of maybe re-appropriating some of these things. If energetically these objects were either made or collected in the spirit of discriminating against people, or representing people in a way that enabled other people to look down on them — to take them out of the context and make them the fuel for something that forces —

NC: I think you hit it right on the nose with the word “fuel.” I mean, that’s really what these object provide: a level of motivation. It provides me this way of tackling really hard issues, but in a way where I’m taking you by the hand on a journey, where you and I can have a one-to-one conversation. It’s not about me being angry, it’s not about me filled with frustration. It’s just really sort of using these objects as a teaching tool.

SRS: Yeah. Sometimes I’m very drawn to objects as evidence of something. I’m gathering evidence— and I might not know for what yet, because it’s almost like being a detective. You’re picking up evidence that eventually you sort of make a case for something.

NC: Yeah, I mean, that’s exactly what I’m thinking about when I’m shopping. I have had things in my studio for, like, two or three years. Just these things that are so profound, but I tend to buy things that have multiple readings — we could read it multiple ways, if it was turned upside-down — and so I will just hold onto them until they find their way into my work.

SRS: That sounds like so much fun.

NC: It’s really amazing.

SRS: And then, the Trayvon Martin piece [“TM13”] is incredibly poignant. I know that you made your first Soundsuit in the wake of the Rodney King beating, as a way of reconciling some legitimate fear on your part, or vulnerability, of your own body.

NC: Right, exactly.

SRS: And this piece really strikes me as what would he have needed around him to make him not so threatening. Like, if Jesus was there, if Santa Claus was there?

NC: And those forms are all these sort of blow-molds that are placed in our yards as a form of celebration. It speaks about an innocence; it also speaks about a certain class. And so I’m thinking about all of these things, surrounding him with these points of entry — there’s a naïveness, there’s an innocence there, and yet there’s sort of refinement, this restraint, this repression. And not necessarily on his part — that’s been placed on him. And I think about how, you know, I operate in these neighborhoods all the time. Sometimes I’m staying in someone’s home, and I may be working at a museum, but I say, “I’m going to walk home tonight.” And I put myself in his shoes, I literally walk home in neighborhoods that are not — it could be there’s a minority family, but most likely not, and I could be placed in that situation. And what do you do? It changes how I operate in the world, you know?

SRS: Absolutely.

NC: To be trapped. To be tied down. To be denied life. It’s so insane right now. I can’t even process it. I can’t even keep up with it. Because, you know, it’s just — I think about the Rodney King, and I think about the Trayvon Martin, I think about Ferguson, and I just think — it’s not that the story changes.

SRS: Right. And that’s shocking, that you were making this work in 1989, and that we have not made very much progress. Now maybe the only progress is that it’s a more visible problem?

NC: Because we have technology to catch things. But there is still this separation from it — “That’s not my reality. This is, over here.” So there’s still this submissive kind of detachment — I’m not sure what we’re doing at the moment, about that.

SRS: I heard about your project coming, and knew that it was going to be unfolding over the course of this year, and then all of sudden it’s like story after story of these situations coming up, with cops and with young black people — and it seems like a very good call-to-action moment, to have all these works here, and to be interacting with Detroit in this way.

NC: As I was saying, with the Ruth Ellis Center — it was amazing working there. It was amazing for the choreographer to be working with the kids, just that alone is amazing. You know, we all want to feel that we matter. We all want to feel that we can make some sort of contribution to the world, and not be dismissed and battered and discriminated against. It’s all of these sort of things. But we also wanted to bring awareness to the center, and it was amazing the extent of support that they received from people that didn’t know what the center was about. So there’s a lot of things happening, and a lot of outcome coming from this project that we hadn’t even anticipated.

SRS: It stands to reason; these works are so instantly gripping. There’s this movement aspect to them, this kind of crossing of genres, this physicality to them that’s completely destabilizing — and it’s good. The world could use a little destabilizing.

NC: Yeah, I think there’s this level of commitment, there’s a level of taking something on and really wrestling with it a bit. And not that you need to understand everything; it’s just about being heard.

SRS: Yeah. “Here, hear.”

NC: What that does for the audience, how that changes the audience, how you can be moving through this exhibition, before you know it, you’re talking to a stranger about maybe a material that’s been chosen for the work that you all can identify with. So again, there’s all these connections, nostalgic sort of memories or connections that allow us to expand on how we are operating.

SRS: Find common ground.

NC: This time around, the people that are in Detroit want to be in Detroit — so it’s a different type of commitment that I’m feeling.

SRS: There’s been such a failure of city systems, in Detroit — what I respond to here is this kind of human infrastructure that has sprung up in its stead. When something goes wrong, I don’t call the cops, I call my neighbors.

NC: Exactly. And I think that’s what I’m saying — the people that are here, that want to be here, are here because they care about the city, they care about the people on their block. They’re in it collectively, and it’s really just a different kind of mindset. You cannot be here, and not be part of the team.

SRS: That’s exactly right. And if you do that, if you just show up and try and set up camp, your gear will be gone the next morning.

NC: You cannot — because, you know what? People need to know that you’re here to help. If you’re not here to help, you shouldn’t be here.

SRS: There’s this weird pioneering thing happening with newcomers — it’s like, come here and do whatever you want. No. Come here and help out. There’s a lot going on already. Everybody needs a hand.

NC: Yeah. You can still do what you want, but also understand the law of the land.

SRS: That’s right. I came here and it really took me a long while of being here to understand what I could bring in — but for a while, it was just being a servant in this house.

NC: Yeah, exactly. Standing back, listening, and looking, you’re going to learn all that you need to learn — because it’s all right there in your face. At the [second performance] Dequindre Cut, you look around, and it’s like, wow, all these people are here for this performance, for a choreographer that lives here, that works with these dancers here — the city is really on board. People want stuff to happen. And there were so many people who had never been down there, and didn’t know that even existed. And it is fabulous, I must say.

Installation view of Soundsuits at ‘Here Hear’. Photo by Sarah Rose Sharp/ Hyperallergic.

From the first Dance Lab performance at the Ruth Ellis Center. The Center serves LGBTQ youth that have been displaced from their homes or families due to discrimination or abuse. Photo by Sarah Rose Sharp/ Hyperallergic.

From ‘Made by Whites for Whites,’ details from some of Nick Cave’s non-Soundsuit works, which deal with found objects reflective of a racial stereotyping. Photo by Sarah Rose Sharp/ Hyperallergic.

Nick Cave speaks to the crowd of hundreds, packed into the Ruth Ellis Center performance space. Photo by Sarah Rose Sharp/ Hyperallergic.

Installation view of Soundsuits at ‘Here Hear’. Photo by Sarah Rose Sharp/ Hyperallergic.

Source: Hyperallergic

Media Inquiries:

Julie Fracker

Director of Communications

Cranbrook Academy of Art and Art Museum

248.645.3329

jfracker@cranbrook.edu.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.