Was it one of the iconoclastic rock ‘n’ roll innovator’s greatest works, or was it his most flawed statement this side of Lulu? Was the double album a carefully crafted work that expanded on experiments made by the founders of minimalism a decade earlier, or was it a hastily conceived barrage of senseless noise? Did he really expect this caterwauling double album of loud feedback soup to be released on RCA’s classical label Red Seal, or did he simply turn it in as a way of flipping off The Man — fully intending for this mess to upset his label enough that they’d break his contract with them?

The answer to each of those questions is most likely somewhere in the middle. We do know for certain that Lou Reed’s 1975 double album Metal Machine Music (RCA) was reviled by rock critics upon its release, and that most copies were returned, unsold. And we also know that since then, it’s come to be understood as an important if idiosyncratic link between 1960s minimalism in New York and later developments in industrial and noise musics. We know that it’s often referred to, but rarely actually listened to.

I am a pretty big fan of the record, having spent a large portion of the summer between 10th and 11th grades actively studying it. I’d come home to my parents’ house and listen to MMM almost every day, after working on a yard crew in the Florida sun, where I wielded a loudly buzzing weedeater all day. The effort began as a challenge, and ended with me finding all kinds of pretty little seagull-sounding flourishes and repeated melodic themes inside of it. That was quite the Rothko Chapel-level revelation, because at first it did seem to be an uncompromising and indiscriminate wall of squealing shit.

I put my brain through this torture because this wasn’t just any difficult record, it was Lou Fucking Reed’s noise experiment. And in seventh grade it hadn’t been easy to digest that first album by his band, the Velvet Underground, either. That thing also scared the crap out of me, at first. But Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia said it was incredibly important, and poetic. And I desperately wanted to be a cool and poetic guy, so I had stuck with that caterwauling, decadent freak scene until it revealed itself. And then all of a sudden, most other music sounded just ridiculous at best. You know the drill of course, whether you were deep into that stuff in fifth grade yourself, or first heard it five months ago.

No one is saying that Metal Machine Music is on the same level as The Velvet Underground & Nico. There’s a certain amateur quality to MMM, after all. And sure, today I know that there are better pre-punk noise records than Metal Machine Music, better loud and weird drone records, better records inspired by La Monte Young, better records made by a speed freak with a weird haircut, and better records made up largely out of feedback. But it’s still a great and significant work. And probably the only reason I know about the other records similar to it is because I devoted that time to MMM in the first place.

Metal Machine Music was recorded by Reed himself in a large loft in Manhattan in 1974, direct to a four-track. Most of the sounds were created by alternately tuned guitars set against amps using different levels of reverb; as the album’s Wikipedia entry eloquently states, “the feedback from the very large amps would vibrate the strings — the guitars were, effectively, playing themselves.” Sounds were layered and often sped up to create the work. The largest single influence on the work is understood to be the drone-based music of reclusive composer La Monte Young; both original Velvet Underground members John Cale and Angus MacLise (the drummer before Mo Tucker joined) had played with Young.

Musician, composer, director of licensing for the Alan Lomax Archive, and archivist Don Fleming bought MMM when it was released. “I sat in my room at home and listened to it on headphones, over and over,” he says. “I didn’t really understand the effect, but I knew I liked it. Many years later I was able to experience La Monte Young’s Dream House and by then I knew that what Reed had achieved was no joke or ‘fuck-off’ to his label or fans, but a valid process that put the mind into a trance-like zone.”

Imagine my glee, then, upon discovering that Cranbrook Art Museum was to present the audio installation of Metal Machine Trio: The Creation of the Universe, “a 3-D sound installation inspired by Lou Reed’s controversial 1975 double album Metal Machine Music.” A giant cube was constructed; it dwarfs the front hall of the Cranbrook Art Museum. It is black and matte, inside and out. The lighting is subdued, making it hard to establish its exact dimensions. It has a 2001 monolith quality to it. Special sound-dampening insulation was used, which has a black hole effect to it. You can’t hardly hear yourself speak inside that cube, even during those brief moments when the installation is quiet.

As you enter the space, your ears are forced to adjust to not only the loud sounds, but to a strange sensation that the sounds themselves are spatially moving around. This is described as “an ambisonic arrangement to create a fully immersive sound experience.” This method of recording was highly technical, fancy, and expensive. When you first step into the middle of the funny-smelling dark space, it’s a little bit like stepping onto a large empty boat, just you there in the middle of it. Hopefully you get to visit the installation when no one else is there, at least for a few minutes, and can stand right in the middle.

Eventually you get your bearings, and you realize that the sound has all been recorded from the perspective of Reed himself, and this is a live concert recording. The recording used in Creation of the Universe originally took place at the Blender Theater in New York in 2009, over two nights. It’s not Metal Machine Music playing in the space (even though that was initially released in a quadrophonic version). It’s an improvising trio of Reed (guitar, continuum fingerboard, and electronics) Ulrich Krieger (electric saxophone, electronics), and Sarth Calhoun (electronics, continuum fingerboard), occasionally joined by John Zorn on the non-electric saxophone.

This is a live recording of Reed with two other musicians, revisiting the greatest commercial failure of his lifetime, toward the end of his life. One of the people onstage originally made the record they were loosely basing their noise jam on, while another, Krieger, had actually painstakingly taken apart all the squalls and squeals of the original double album in order to transcribe it fully.

The full orchestral arrangement of Metal Machine Music undertaken by Krieger at the start of the century and later recorded with the experimental music ensemble Zeitkratzer is actually what led to Reed’s creation of the Metal Machine Trio in 2008. Reed clearly felt that it vindicated his experimental work, which has been dismissed as a joke upon its release.

Fleming, who has been working as the archivist on Reed’s collection for the Reed estate and assisted with the exhibit catalog, is a fan of the Trio recording. “The real foundation of the sound is the droning guitars,” he says. “Having Reed, Krieger, Calhoun (and at one point Zorn) improvise over the drones was an added layer of sound that the original didn’t have. That was a neat way to perform it, and it was great to see Reed embrace the piece again, especially since he had never performed it live.”

The installation was originally presented by the University Art Museum at California State University, Long Beach in 2012, and Reed closely collaborated with the acoustic specialists at the Arup SoundLab in New York to fine tune it. Reed fell in love with the final work, which has been faithfully reproduced at Cranbrook. There is a moving photo in the excellent exhibition catalog of Reed sitting in the middle of the space, a smile etched onto the lines of his face.

“I did this installation for Cal State University, Long Beach,” says Cranbrook Art Museum director Christopher Scoates. “We did it in 2012, when Lou was still alive; this is the second iteration of this project. When we did it in Long Beach we actually took a room of the museum and soundproofed it, and [here], we built a room for it specifically. The idea was to put this piece in a historical context because Lou wanted to be considered a serious composer with our presentation. We did a John Cage show here in the ’70s, we did a show with Yoko Ono in ’93, and we plan on doing more projects like this in the future.

“And the idea here is similar to La Monte Young’s Dream House, where you can come and go, and there’s no beginning or end; you can drift into that piece. That’s very similar to this; there’s no compositional structure that allows you to sit from beginning to end. This will run all day, and when the museum is open you can come and go as you please.”

When the Velvets harnessed feedback to their own nefarious genius in “Heard Her Call My Name” or “Sister Ray,” it was in the service of a pop song, even on the most extended versions of either. Reed was one of our greatest rock musicians, hands down. But when it comes to purely abstract and experimental noise music, his work in that field doesn’t fully cohere. The music in Creation of the Universe, as good as it often is, is fundamentally an old guy garage noise band. This work at best approaches Neil Young’s Arc record, another interesting old guy feedback work that’s cool enough, but wanky.

The work has been installed in the Cranbrook Art Museum since Nov. 21. It’s easy to see how the work of the Metal Machine Trio was a personal milestone for Reed, and a homecoming back to the volume-saturated work of his youth. I’m sure these shows would have been very satisfying for die-hard fans. It’s a little bit of a shame, however, that for this installation, neither the actual Metal Machine Music music was used, or the orchestral version of it. It’s a bit like mounting a huge exhibition around a famous painting, and then only showing a later version of that painting — redone years later, from memory.

“The cool thing about the recording is that Reed worked closely with the acoustic specialists at the SoundLab to re-create exactly the same acoustic perspective he had while performing it onstage,” Fleming says. “Reed was the ultimate gearhead and it reminded me of his recordings in the 1970s done with binaural sound to achieve a 3-D stereo sound. In that case, it only worked when listening back on headphones. With the Arup ambisonic sound installation, they use 12 speakers so that you experience the 3-D sound in the room without headphones. Reed loved it.”

Raj Patel engineered both the original recording and the installation of the piece, along with his colleague Mike Skinner. “After hearing about five minutes of it, [Reed] asked us to pause and said it was ‘the best fucking live recording I have ever heard,'” he says. “The recording was made with a special 3-D microphone placed right by Lou’s head, that picked up the exact direction, loudness, and time arrival of reflections as experienced by Lou during the concert. The playback is over a 3-D sound system that allows reproduction of the recording exactly as it was heard.”

If you haven’t already, carve out some time by March 26 to experience Creation of the Universe. It’s at the very least a highly engaging novelty, a thrill ride for at least one of the senses (the smell of the chemically saturated panels is a bit weird, but that’s typical for installations of this sort). We recommend that you drop by before March 13, as that’s when the concurrent installation of Andy Warhol’s epic film Empire (1964) ends. There are multiple resonances in that very smart pairing, of course. “I compare them in the catalog; it’s all about duration of aesthetics,” Scoates says.

“It goes eight hours, and you can come and go from that piece when you want, as it’s one long take. I consider that a sort of visual drone, where this is sort of an audio drone. And Warhol talked to Lou about Metal Machine Music in ’75 and asked him, ‘Why does the music have to stop.’ Right? And then Lou added a locked groove to the end of side four, so you can let it play forever.”

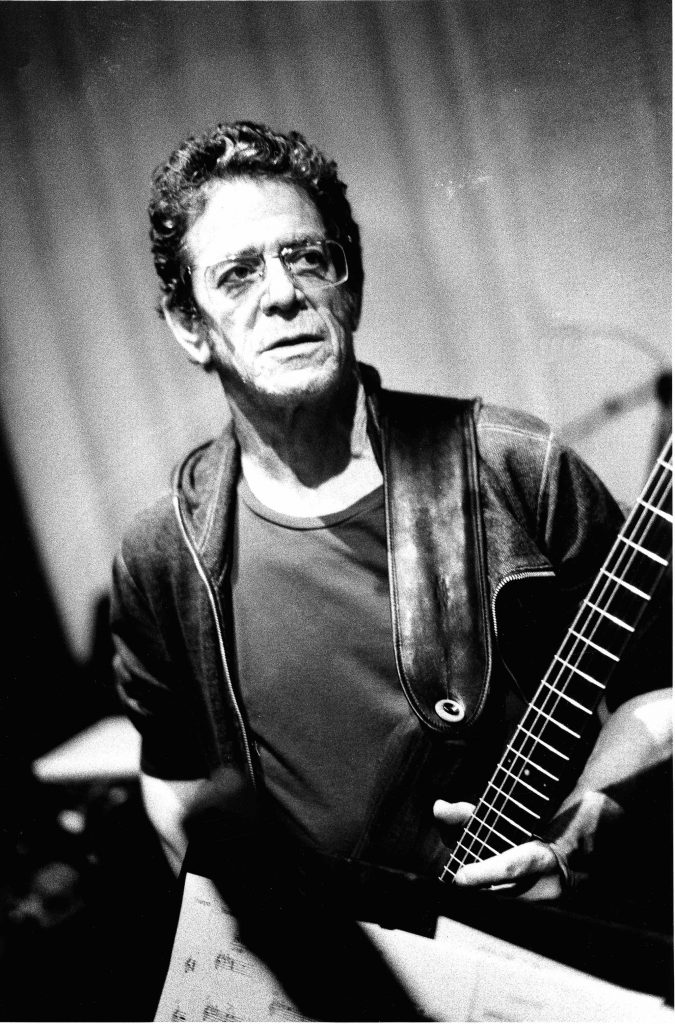

Photo by Ralph Gibson

Source: Detroit Metro Times

Media Inquiries:

Julie Fracker

Director of Communications

Cranbrook Academy of Art and Art Museum

248.645.3329

jfracker@cranbrook.edu.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.