BLOOMFIELD HILLS, Mich. — Sometimes, taking a wider view of art history can create a more expansive curatorial vision. Previously the senior curator of Design, Research, and Publishing, and later the curator of Architecture and Design at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Andrew Blauvelt developed a wider take on which elements of cultural production contribute to art movements. He brought this perspective to Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, an exhibition that was five years in-the-making before it expanded into the Walker’s 14,000 square-foot floor plan in 2015. Hippie Modernism (with the exception of a few artworks) is now at the Cranbrook Art Museum, following on Blauvelt’s heels in his new appointment as the director of the museum. The exhibition offers a fascinating look at the merging of hippie values with a modern design sensibility and how it sparked unique cultural production far outside the highly commoditized art market inflamed by Pop Art.

“From a design perspective, it’s all the creation of artifacts, the creation of the lifestyle — so all the accessories or the props, in some cases, that would be necessary to stage post-revolutionary life,” said Blauvelt, defining Hippie Modernism as a movement, in an interview with Hyperallergic. “As a designer, I understand that design is always prototyping things — it’s a modeling exercise, basically. Your building is going to look like this, your brand will look like that — and it’s the same thing here, except it’s done for everyday life.”

The first seeds for the show were planted by Blauvelt’s chance encounter with the term “Hippie Modernism,” mentioned in passing by Lorraine Wild in the context of the Cranbrook Academy of Art’s design program of the 1970s. Blauvelt revisited the concept as he became interested in the Italian radical architecture movements, with well-known contributors such as Archizoom and Superstudio, as well as other, more fringe, activity. “You [only] get so much space, as a curator, and the Italian radical architecture was sort of going to be a smaller show,” said Blauvelt, “And then they just kept adding more galleries [at the Walker].”

Hippie Modernism is a far-ranging and detailed encounter with the collective cultural production of the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, presenting hippie culture in a global context, and highlighting the design, political, and conceptual underpinnings to a movement that is often better remembered for its more frivolous music, drug, and fashion culture. This is perhaps due to what Blauvelt refers to as “the two erasures” — within architectural history in the 1980s, and within art history in the 1970s — where a great deal of the cultural output was not designed for galleries or museums, but integrated into civilian life. As a result, the movement was discarded as ephemeral or dismissed for having kitsch aesthetics, but Blauvelt sees a resurgence of interest in the cultural production of the hippie modernist era, in part because it has not been as chronically over-mined and surveyed as other contemporary movements, such as Pop Art and Minimalism.

Indeed, it is refreshing to see such a broad slice of the cultural appetite of this era. Arguably, hippies were opposed to modern society, in terms of their interest in archaic forms of communal living, off-the-grid sensibilities, and questioning of culturally enforced norms. Yet their solutions to these issues were addressed in the most modern design terms: geodesic domes, modular structures and garments, as well as an interest in personal computers as vehicles for self-expression (rather than tools of war, as they were originally designed). Blauvelt characterizes Hippie Modernism as capturing a movement very much counter to the reductionist aesthetics of color-field painting and Minimalism, but, in a sense, hippie modernism’s maximalist design principles and social interventions were contributing to a bigger push for simplifying and streamlining lifestyle.

There are relatively few objects on display in Hippie Modernism that can be considered standalone art pieces: paintings by Isaac Abrams, the giant inflatable finger sculpture, “Roomscraper” (1969) by Haus-Rucker-Co, perhaps “The Ultimate Painting” (1966/2011) by Clark Richert, Richard Kallweit, Gene Bernofsky, JoAnn Bernofsky, and Charles DiJulio – a psychedelic mandala spinning in a darkened geodesic half-dome, which viewers can experience by pushing buttons to activate a strobe light at different hypnotic frequencies. The galleries are dotted with experimental film works, such as Bruce Conner’s “BREAKAWAY” (1966), or psychedelic films combining light patterns and music in viewing rooms (helpfully outfitted, in some cases, with beanbag chairs).

Much of the rest of the work on view not only holds aesthetic value, but informational and use value, as well: copies of the Whole Earth Catalogue; Evelyn Roth’s installation pieces made of recycled thrift store sweaters; innumerable plans for portable living spaces; and a working prototype of a modular Relaxation Cube from Nomadic Furniture 1 — a 1973 design book by designers Victor Papanek and James Hennessy — with floor cushions and a charmingly retro slideshow. Speaking of slideshows, the pièce de résistance is a reconstruction of “The Knowledge Box” (1962/2009) by Ken Isaacs: an immersive two-and-a-half-minute inundation of political and cultural imagery inside a cube equipped with 24 slide projectors firing away at every surface. Bringing the exhibition full circle to its impetus, “The Cranbrook design trip” (1973) is on display — an illustrated “map” that details a Detroit–New York road trip undertaken by Katherine McCoy, Edward Fella, and a cohort of their Cranbrook design students.

If you manage to wend your way through the exhibit, the reward waiting for you in its furthest reaches is an installation piece by Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida, “CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress” (1973). Equipped with projections, hammocks, and crashing 1960s rock and roll, the installation offers the perfect environment for chilled-out contemplation of all one has seen.

Hippie Modernism effectively captures a time when the seemingly disparate value systems of radical politics and modern design made an unsteady truce in search of social progress — which makes it perhaps a timely moment to revisit in light of our increasingly divided nation. Certainly, Cranbrook’s idyllic campus — at once a rejection of the travails of the wider Detroit Metro area and at least a passive beneficiary thereof — is a fittingly ironic setting for these utopian dreams.

It was striking to me that much of the ground covered in this exhibit might today be considered “social practice art,” leaving me to wonder if the art world has gotten more progressive in its understanding of the role art plays within society, or if the capitalist machine has simply gotten better at using art to reach out and appropriate movements before they can effectively challenge systems. Overall, Hippie Modernism paints a picture of radical and rhizomatic action, taking place on a global scale and largely independent of controlling interests. Hippies are often characterized in retrospect as being hedonistic or frivolous in their lifestyle, but Blauvelt has done the work of an art historian well and truly, excavating not just representative works, but an entire world that seemed, for a shining moment, to be designed for collective betterment. It is a heavy trip to consider what design we are currently living out, in a society that seems increasingly tilting toward dystopia.

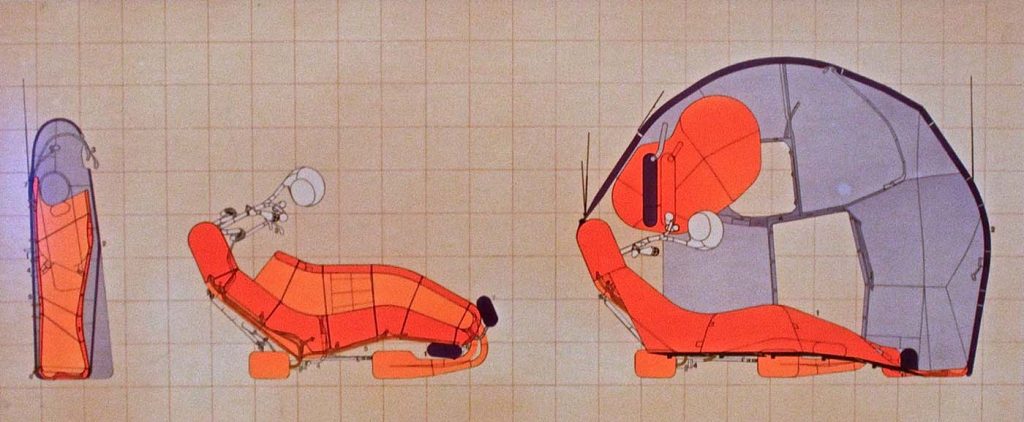

Archigram (Michael Webb), “Cushicale—Opening Sequence” (1966)

Works by Haus-Rucker-Co, installation view

Boyle Family, “Beyond Image and Son of Beyond Image” (1969), installation view

Haus-Rucker-Co, “Roomscraper” (1969)

Psychedelic posters and printed matter, installation view

Evelyn Roth, “Family Sweater” (1974)

Ken Isaacs, “The Knowledge Box” (1962/2009)

Source: Hyperallergic

Media Inquiries:

Julie Fracker

Director of Communications

Cranbrook Academy of Art and Art Museum

248.645.3329

jfracker@cranbrook.edu.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.