BY KELSEY CAMPBELL-DOLLAGHAN

Image: PD Rearick/courtesy Cranbrook Museum

Punk, and its associated subcultures, revolutionized design practice. A slew of new shows and books reckons with its impact.

Do you remember the first zine someone put in your hands?

If you lived through punk’s heydey, or any of the subcultures that reverberated down from its birth to echo into the mid-aughts, you probably came across more than a few of them. Variable in quality, self-printed, gratuitously niche, and often full of self-referential winks, zine culture existed at a precise moment when computers were becoming more common, but social networks hadn’t yet made the notion of communicating with your peers on paper irrelevant. They mixed DIY culture and nascent technology with music and art. You sent away for them, hoarded them, and published your own responses, even if you were a high schooler imagining a culture thousands of miles–and probably a decade or two–away from your own.

They were outsider design. But the zines, fliers, and posters produced by punk and its associated subcultures were hugely influential to design practice itself, in ways that are only now, 40 years later, being given a closer look by historians and curators. Earlier this spring, a visual history of club culture published in the U.K. considered the impact of dance music on design. Vitra Design Museum is currently staging a show on the design of nightclubs in the ’70s and ’80s and how they influenced gentrifying global cities. And at Cranbrook Art Museum in Michigan, the curator and designer Andrew Blauvelt is opening a comprehensive exhibition Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die: Punk Graphics, 1976-1986, on June 16.

Blauvelt grew up in the Midwest and went to school at Cranbrook during the era his show reckons with. It shows: The exhibition’s publication is an oversized, three-part zine of sorts itself, printed on newspaper, that’s as fun to read as it must have been to put together. In it, he talks about the mood in design at the time. “[Punk was] an inescapable soundtrack that filled the air of painting studios in the days of the boom box, or one’s ears dutifully plugged into a Sony Walkman,” he writes. “I think a lot of graphic designers were influenced by [punk], because they were listening to the music in school, and buying the albums, and being part of that culture,” he adds over the phone. “You would have been exposed to a lot of this stuff. So it gets all mixed up, and I don’t think it’s really been untangled.”

Blauvelt’s show is doing the work of untangling it. The exhibit’s collection of graphic ephemera from the era investigates the visual strategies used by musicians, fans, and designers, too–from appropriation to influences from comics and social protest movements. It also suggests a fascinating framework for how the punk ethos influenced design history.

While the concept of “deskilling” in design–in which the computer democratized the tools of design and opened the profession to new experimentation and rule-breaking in the late 1980s–has been around for a while, Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die argues that process began well before computers, in the 1970s, when punk’s creative ethos began to permeate design culture. “The kinds of rule breaking that was happening aesthetically and typographically was being done because they couldn’t care less or they never learned the rules,” Blauvelt says. “That was highly influential on graphic design practice proper. People now talk about deskilling, but they usually reference that in terms of the personal computer and how it made everyone a designer . . . But punk does this before the computer.” After all, it was still the early ’70s when the type designer Wolfgang Weingart’s distinctive approach to “blowing apart” the rules of Swiss Style earned his work the popular moniker “Swiss Punk” (even if it was created by a professional).

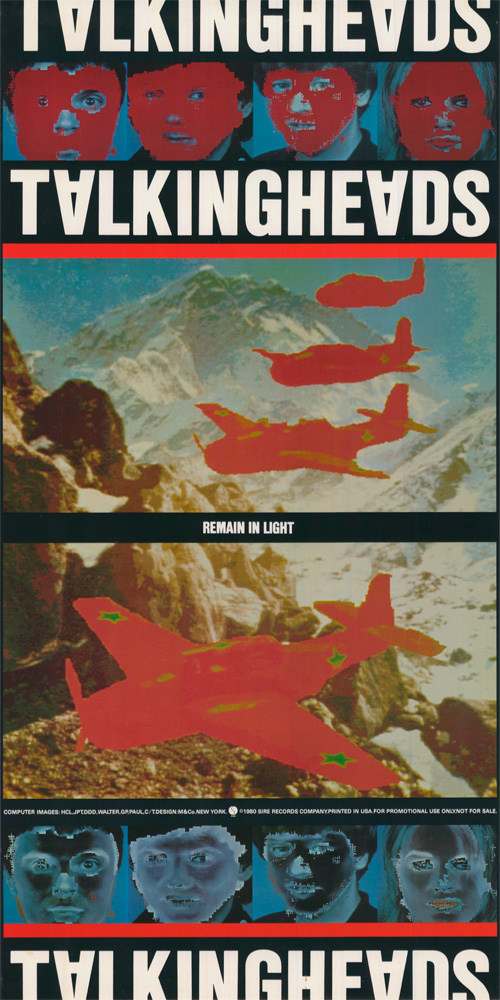

Culled from the sprawling archives of punk ephemera collector Andrew Krivine, the pieces in Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die range from punk proper–like the work of Jamie Reid for the Sex Pistols–to selections from Peter Saville’s work for Factory Records, Joy Division, and New Order and the Talking Heads’ album Remain in Light. The art for that 1980 classic was designed by band members Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth along with Tibor Kallman. An image of the Himalayas, with a fleet of red warplanes foregrounded, graced the back side of the album. The art was created with the aid of early computers from what would become MIT Media Lab, and guidance from MIT technologists Walter Bender and Scott Fisher. Its use of computers sets it apart from many of the other pieces, but its underpinnings are the same; it’s a vivid mix of appropriation and agitprop created by a mix of trained and untrained designers.

Remain in Light–LP poster (1980) for the Talking Heads. Tibor Kallman design. [Image: Warner Music/courtesy Cranbrook Museum]

Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Diearrives accompanied by a constellation of other new exhibits and books that reckon with the same era, raising a simple question: Why now? Is it that the designers, curators, and critics who grew up during these years are finally old enough–and possessing of the cultural capital–to give punk rock the intellectual attention and curatorial space that an older generation hasn’t? Or is that we’re living in a time when sociopolitical mores mirror those of the late ’70s and ’80s, making this work relevant in a new way?

Rick Banks, the designer behind the book Clubbed, a compilation of the design culture of clubs from the ’70s to the ’90s, points to timing–and the fact that nightclubs and music venues, while less popular, are still important cultural hubs. “If you look at the numbers, clubbing is definitely on the down, but I think people want to show councils/property developers that club culture matters and is hugely important,” he writes. “I also think . . . the right amount [of] years have passed to look back and be nostalgic. Especially when we are are seeing ’90s music being played in modern-day DJ sets.”

Blauvelt nods to the transgressive practices of the era, and how a younger generation of designers are now being influenced by the work. “There’s cultural permission to go into these spaces,” he says. Likewise, he adds, “I think there’s a lot of interest from younger designers in this period, even stylistically.”

Punk itself was remarkably short-lived, of course. In some ways, it was eclipsed by its ethos–and its visual strategies–which lived on in post-punk, house music, ska, goth, and a family tree of other descended genres. It also lived on in design, where rule breaking and DIY tactics became de rigueur in design schools and practice. You can still see its fingerprints in the maker movement, for instance–as well as in the net art movement and the resurgence of interest in New Wave design. “Although punk may have been too fast to live,” Blauvelt writes early on in the show’s publication, “it was not, however, too young to die.”

Read the full article here.

Media Inquiries:

Julie Fracker

Director of Communications

Cranbrook Academy of Art and Art Museum

248.645.3329

jfracker@cranbrook.edu.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.