Bloomfield Hills, Mich., June 4, 2024 – This summer, Cranbrook Art Museum will present a comprehensive set of exhibitions surrounding Cuban mid-century design that tell the story of a lost generation of artists, architects, and designers.

The headlining exhibition, A Modernist Regime: Cuban Mid-Century Design, is the first comprehensive museum exhibition dedicated to the design movement and will feature objects never exhibited outside of Cuba. The exhibition opens at Cranbrook Art Museum on July 11, 2024, and will run through September 22, 2024.

It will be accompanied by a two-part exhibition series, A Modernist Regime: The Cuban Contemporary Lens, which focuses on exiled Cuban artists and designers responding to Cuba today. These exhibitions will close on September 1, 2024.

A Modernist Regime: Cuban Mid-Century Design focuses on the decades immediately following the Cuban Revolution (1953–1959), examining how modernism in design paralleled Cuba’s existential conflicts from the Revolution until today.

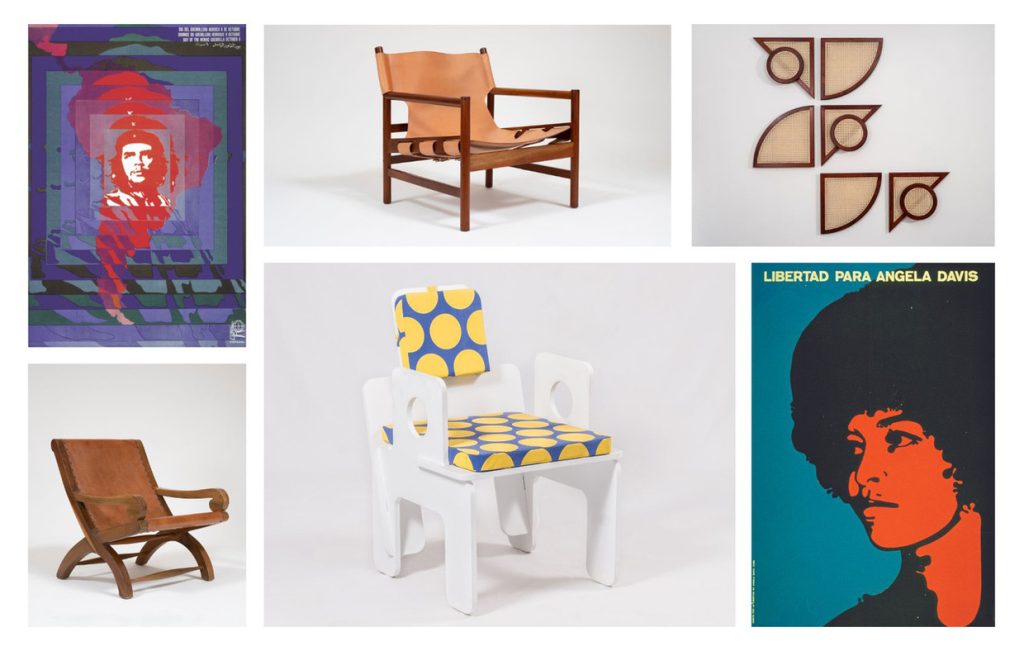

Featuring nearly 100 works, including more than 50 pieces of furniture, it will trace a small but prolific group of architects, artists, graphic designers, and furniture designers whose work reflected the initial optimism of the Revolution through the authoritarian regime under Fidel Castro.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a 240-page catalog (Cuban Mid-Century Design: A Modernist Regime, Rizzoli/Electa, 2024) that will shed light on these overlooked creators and projects. The communist government did not fund, preserve, or document Cuba’s post-revolutionary modernist heritage. This history is narrated by surviving designers, architects, and their families. Both the exhibition and publication bring attention to these important stories.

The groundbreaking exhibition will include objects of functional design, renderings, and prototypes that showcase the “design for all” ideas of the times, including examples of graphic design and architecture that exemplify how modern design could be used to help position the new regime on various international stages.

As Andrew Satake Blauvelt, Cranbrook Art Museum Director, relates: “Since Cranbrook is known around the world as an incubator of mid-century design, we are drawn to narratives of similar developments elsewhere, in this case, from the Global South. Just as designers in the U.S. interpreted the tenets of modern design, so did Cubans, although in a completely different economic, social, and cultural context.” Blauvelt continues: “A Modernist Regime: Cuban Mid-Century Design is a fascinating case study of how modernism was adapted to not only the tropical climate and local materials on the island but also to that country’s diverse racial and ethnic history and the new nation-state’s position and identity in the world.”

A Modernist Regime: Cuban Mid-Century Design is organized into the following sections to explore the eras of design that emerged in Cuba in the 1960s through the 1970s:

Before the Revolution, furniture from European and North American designers, including Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, and others, co-existed in Cuban homes alongside locally designed furniture created by carpentry shops that replicated modernist designs.

After the Revolution, when private businesses ceased to exist, the government created the Dujo company to design and produce furniture for governmental officials and the export market. Under the design direction of Gonzales Córdoba with the assistance of María Victoria Caignet, the Dujo brand followed the trajectory of mid-century modernism that had come before but with a renewed emphasis on the use of native woods and fibers. These designs were marketed in Europe and included in international furniture expos and fairs in the 1960s. This gallery recreates one such vignette.

In the 1970s, as domestic demand for furniture grew and with the island facing restrictions on the importation of embargoed goods and materials, the regime segued from the Dujo brand to EMPROVA, taken from the phrase, “Empresa de Producciones Varias” meaning “Various Productions Company.” Also led by Cordoba and Caignet, EMPROVA furniture employed a modular approach using distinctive dark wood frames with contrasting natural rattan inserts. The exhibition contains several examples of the EMPROVA line, including some small furnishings and accessories.

Also featured in our main gallery are furniture examples by Clara Porset, perhaps the best-known of the Cuban-born designers. Porset had studied in the U.S. and Europe and had brought back to Cuba the tenets of modern design. Due to her leftist beliefs and political activism, Porset had fled Cuba under the rule of Gerardo Machado and became a well-known designer in Mexico, occasionally returning to Cuba whenever the political climate allowed. After Fidel Castro overthrew the autocratic government of Fulgencio Batista, she seized the opportunity to return to her native country. Her return to Cuba would be short-lived. While in Cuba she managed to design and produce furniture for rural schools, several rare examples of which are included in the show.

In another gallery, view the work of the designers associated with the Ministry of Light Industry. At the center of the gallery will be a recreation of a domestic showcase of new furniture prototypes centered on a bedroom storage wall system. Even more concerned with low-cost, easy-to-assemble furniture, the designers of the Light Industry Group embraced a design-for-all ethos and the latest advances in mass production, including the use of particleboard and mechanical fasteners that would eventually become the mainstay of the furniture we today associate with companies such as IKEA.

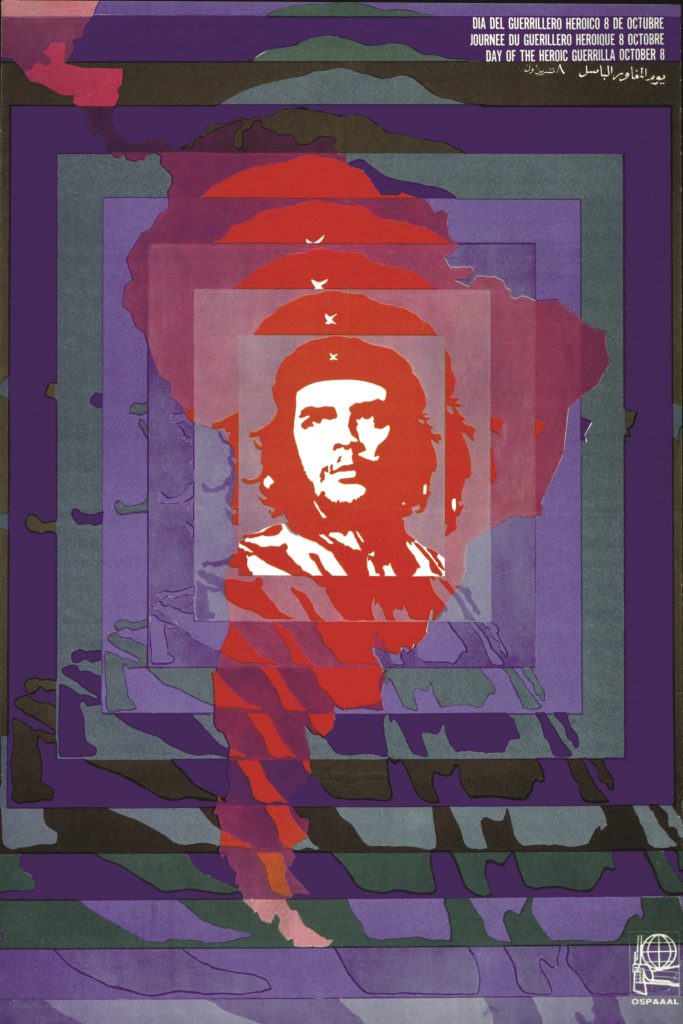

As the Dujo line of furniture was exported to foreign markets, the Cuban government sought opportunities to have the regime take its place in international forums. The exhibition includes poster designs commissioned by the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL), created by Cuban artists, and designers for emancipatory revolutions worldwide from the 1960s through the 1980s. The designs received critical acclaim for their diverse graphic design approach, helping forge Cuba’s unique poster design heritage. Rounding out the exhibition are examples of modern architecture commissioned by the regime to bolster its reputation, such as the geometrically striking Cuba pavilion for Expo 67 (Baroni, Garatti, Da Costa, 1966–67) held in Montreal, Canada; or the experimental “Caterpillar House” (Mercedes Álvarez and Hugo D’Acosta,1964–68), a prefabricated residential dwelling prototype made of molded asbestos-cement panels that featured built-in beds and storage units.

As the initial optimism that ushered in the Cuban Revolution gave way to authoritarian control of society under the Castro government, early design experiments were abandoned and artists and designers fell out of favor with the regime. This trajectory of government control over the production of art, architecture, and design reaches its apex in Cuba today, where artists and other creatives are routinely censored, imprisoned, and exiled.

As a companion to the historical exhibition, the museum will also present two exhibitions focused on the contemporary artists and designers of Cuba.

As part of A Modernist Regime: The Contemporary Cuban Lens, the solo exhibition Marco Castillo: The Hands of the Collector features several bodies of work by the artist and prolific collector of Cuban mid-century design that he initially started to amass while working as part of the artist collective Los Carpinteros (1992–2018). Castillo incorporates the aesthetics derived from Cuban modernism into his practice to resurrect Cuban design history and critique the oppression by the government against artists, designers, and intellectuals in Cuba. Many of his artworks are named after modernist Cuban architects and designers in homage to this forgotten generation of creators. Castillo’s work often references an aerial view of the plans interior designers use to lay out a room but presents the objects in turbulence. The work is a freeze-frame of deconstruction, which conceptually links to the demise of the autonomy of Cuban artists and the loss of creative life within a dictatorship.

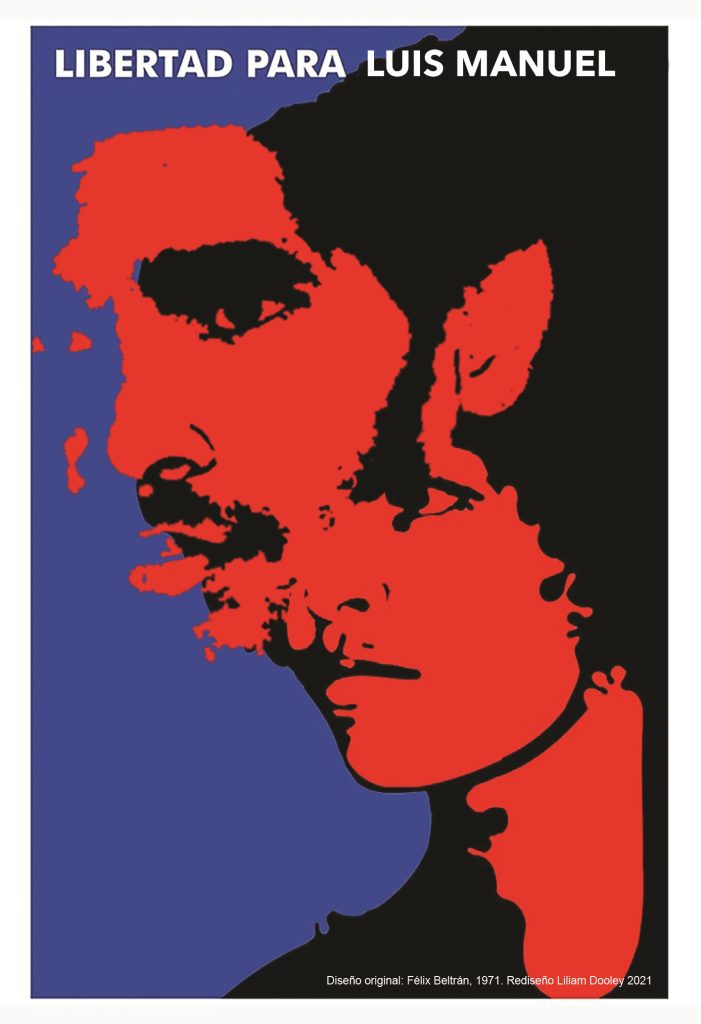

As part of A Modernist Regime: The Contemporary Cuban Lens, the exhibition Cuba Dispersa (Cuba Dispersed) features six artists and designers—Julio Llópiz-Casal, Liliam Dooly, Anet Melo Glaria, Celia González Álvarez, Hamlet Lavastida, and Ernesto Oroza—that respond to the current conditions in Cuba. Currently, none of the artists live in Cuba, with some forced into exile. Over the past few years, the Cuban government has launched a campaign to suppress the artistic community and control creative production through official legislation. As co-curator Abel González Fernández explains, “When looking at Cuba, we must recognize our fascinating, tragic, elegant, and complex Cuban history. What are we going to keep? We may not have a land for all Cubans to be reunited now because of the dictatorship, but we have a shared memory that unites us.” The exhibition features six new commissions, one by each artist, who will mine these design and material histories to highlight the past while imagining potential futures.

Media Inquiries:

Julie Fracker

Director of Communications

Cranbrook Academy of Art and Art Museum

248.645.3329

jfracker@cranbrook.edu.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.