© 2001 The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.

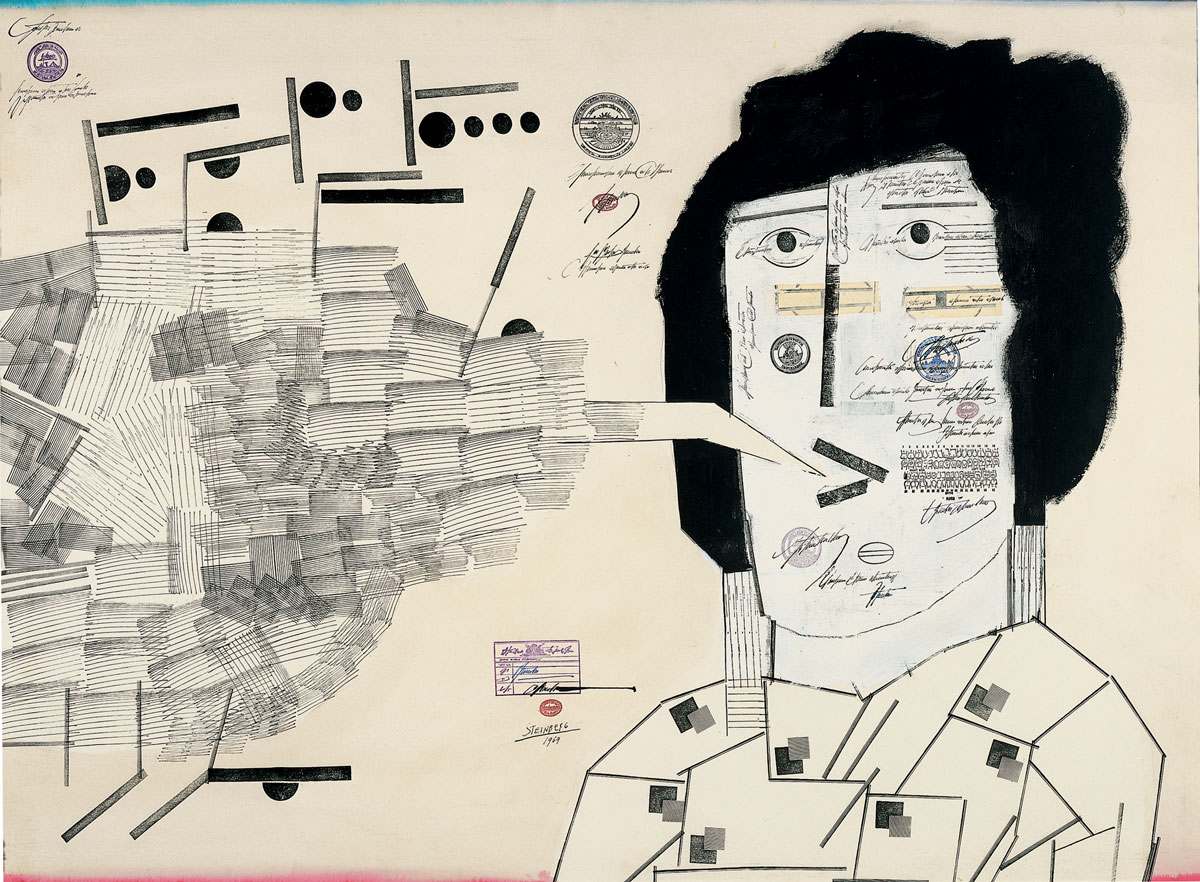

© 2001 The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.Speech 2, 1969

Speech 2, like many of Saul Steinberg’s works, tantalizes viewers by seeming at first a light-hearted picture puzzle filled with visual puns. Quickly one is drawn ever deeper into wrestling with layers of meaning. Steinberg has been called “a writer of pictures” and “a draftsman of philosophical reflections.”

Born near Bucharest, Romania, Steinberg studied sociology and psychology at the University of Bucharest before earning a doctoral degree in architecture at the Reggio Politechnico in Milan, Italy (1940). For him, “The study of architecture is a marvelous training for anything but architecture. The frightening thought that what you draw may become a building makes for reasoned lines.” He published his first “cartoons” during these years in humor magazines and observed that, “In Fascist Italy, where the controlled press was predictable and extremely boring…the nature of humor itself, seemed subversive.” The rising tensions of World War II forced him to undertake a roundabout journey out of Italy, which brought him to the United States in 1942. En route, his first drawings were published in the New Yorker magazine, which sponsored his entry into the USA.

From the beginning, Steinberg’s subject was the wacky disparity between the world and the way each of us sees it. Mark Stevens reported in 1978, “Steinberg thinks of himself as a writer… [H]e speaks five languages fluently, but none perfectly.To write, he must therefore draw, and he likes his pictures to be carefully read.” Steinberg “wrote” with lines, saying, “The doodle is the brooding of the hand.” In Speech 2, lines define details of physiognomy, dress, speech, and indecipherable “official” calligraphy.

Speech 2 presents what could be the omnipresent modern media scene: a “talking head” (of indefinite gender) declaiming officially in some public place. The style is mixed. The hair is a brushy, soft black mass. The chin is limned with a sensitive delicate stroke. The lines of speech are diagrammatic areas of parallel lines, overlapping and angling against each other within the “talk balloon.” Other features are created with stamped lines and emblems. One senses links to some of the multiple visual sources which Steinberg acknowledged: “Egyptian paintings, latrine drawings, primitive and insane art, Seurat, children’s drawings, embroidery, Paul Klee.”

Roland Barthes noted how every “thing” in a Steinberg work represents a representation. In Speech 2, the artist has played lavishly with “signs.” Here, two stamped rectangles, set at a 45-degree angle to one another, become a mouth. A dental chart speaks of teeth inside the oral cavity, a single official record that signifies an individual’s reality in the ordered social world. Here the outer skin of the personage merges with and emerges from the official notations of his/her existence, while the thin washes of red and blue across the upper and lower borders suggest a patriotic flag or badge.

Steinberg was fascinated by the ways in which each of us gains official reality only through our presence in official documentation-passports, identity cards, tax reports, licenses. Fake rubber stamps had served the artist well in successfully “reactivating” an expired passport to help in his escape from Mussolini’s Italy, an experience that continued to inspire him. And bogus rubber stamps validate key areas of Speech 2‘s space and personage, suggesting that the entire work represents a special kind of identity document.

We smile as we unravel the layered representations of Speech 2 at the same time as we shiver at the darker implications of such a “reality.” Here, Steinberg the writer of pictures joins a host of literary authors who saw the world through ironic pens, including Kafka, Moliere, Pirandello, Beckett, and Ionesco.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.