© Catherine Murphy. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh..

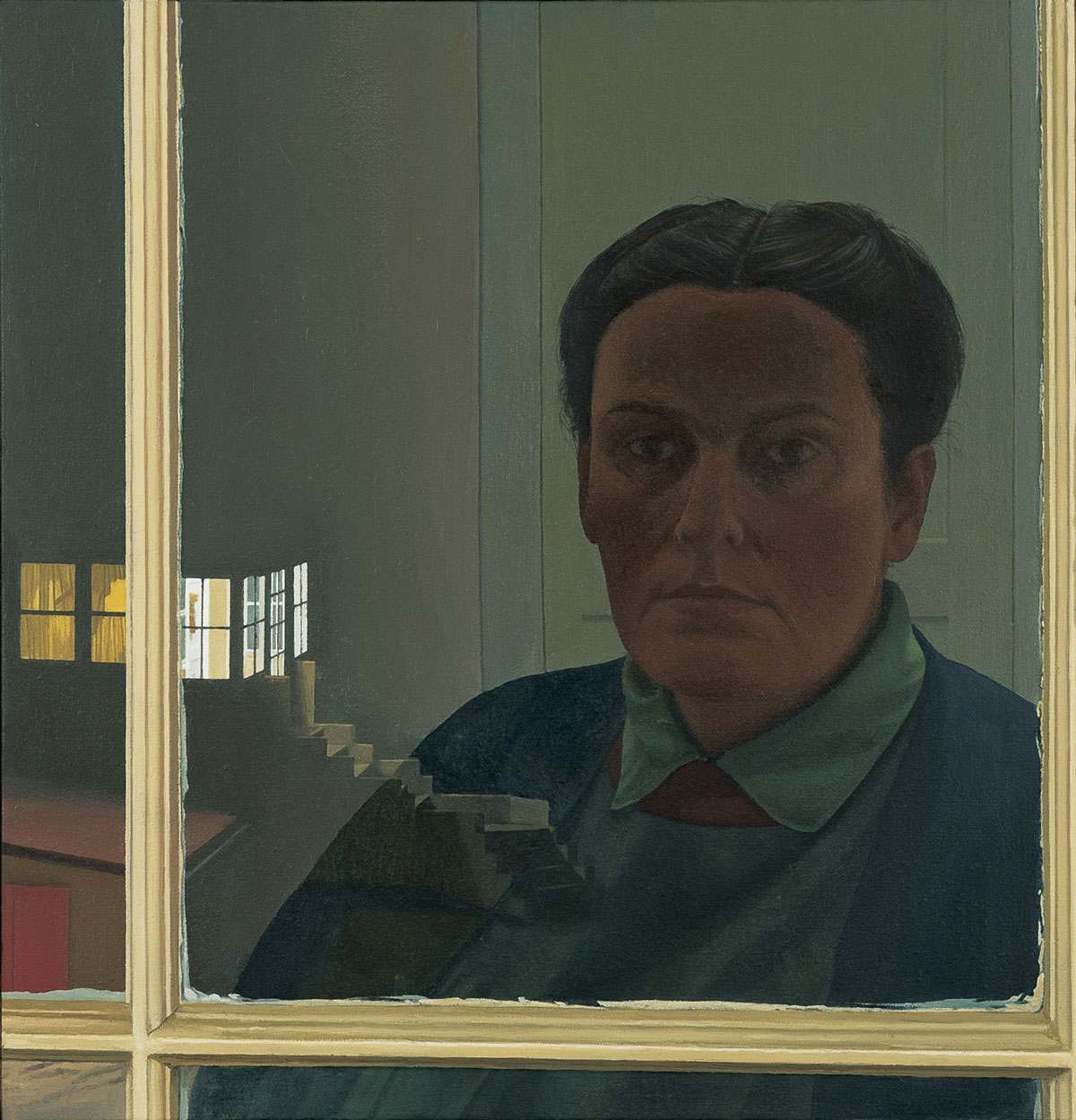

© Catherine Murphy. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh..Nighttime Self-Portrait, 1985

Catherine Murphy’s work has always expressed both her acute perceptions of her personal world and her sense of the geometries underlying its ordinary objects and places. Nighttime Self-Portrait shows the view seen by the artist looking through a nighttime upper window of her house at an outside porch entrance, which intersects with the dim reflection on the glass pane of her face, shoulders, and a bit of interior door and wall. The mullions of the interior window frame are rendered with such illusionistic care that they seem to protrude into our space. This transforms the window’s surface into the picture plane. Catherine Murphy’s reflection places her on “our” side of the picture plane, while through the window “in the picture” lies an assembly of cubic steps and building parts.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Murphy studied at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute (B.F.A. 1967), and spent the summer of 1966 working at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. Early on, Murphy was hailed as a contemporary Edward Hopper, and compared with artists like Jane Freilicher, Neil Welliver, and Fairfield Porter. As an admirer of the spare Minimalist work of Robert Ryman, Robert Mangold and Brice Marden, however, the tension between representation and abstraction is higher in Murphy’s work. She says, “The point of doing figurative paintings is to achieve a balance between content and form…about finding the geometries in what looks like chaos.” To Murphy, geometry is a natural part of human perception of the visible world, a view reinforced by a rectangle she found near a reindeer in a reproduction of Lascaux cave walls. “I realized,” she commented, “that rectangles are in our heads, they’re natural to us.”

In an early exhibition, Murphy hung three works together as Garden of Eden Trilogy, a narrative constructed for the show “about the apple and how Eve, in eating it, gave us all self-consciousness. Without self-consciousness, there would be no art.” In Nighttime Self-Portrait, the translucent veils through which we see into the rear room of the exterior structure recall an early comment by the artist about being “a watcher behind curtains.” Here the painter observes an unpeopled part of her domain from a perch high in her home. Self-portrait details of clothing and physiognomy are rendered with a fine brush, but dulled to capture the mysterious quality of a nighttime reflection. Our attention is caught by the off-axis framings of the crisply-focused window mullions, which are echoed by the dim verticals of the door jamb behind her figure, and counterpointed by the showy illuminated cascade of shapes in the yard below.

Although at first glance, one might say Murphy’s paintings are “photographic,” she prefers to work directly from her chosen subject. The result is not a painstaking record of a scene frozen in time, as in a photograph. Rather, the artist says that her works “show what I was seeing changing in time.” The viewer catches hints of this time-vision in incongruous details in Nighttime Self-Portrait, like the sudden jog in the upper frame of the window to the left of the lighted porch’s entry door, or the mismatch between the top of the red door and the roofline of the attached “garage” below the lighted rooms. This is a magical world. Murphy’s works are, as Linda Nochlin wrote in 1985, “charged with a very contemporary awareness of the ambiguities of the domestic, of the ways, both dramatic and subtle, that the known shades into the mysterious, the personal into the objective, the cozy into the uncanny.”

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.