Courtesy of the Estate of Joseph Hirsch and Kennedy Galleries, New York. Photograph by R. H. Hensleigh.

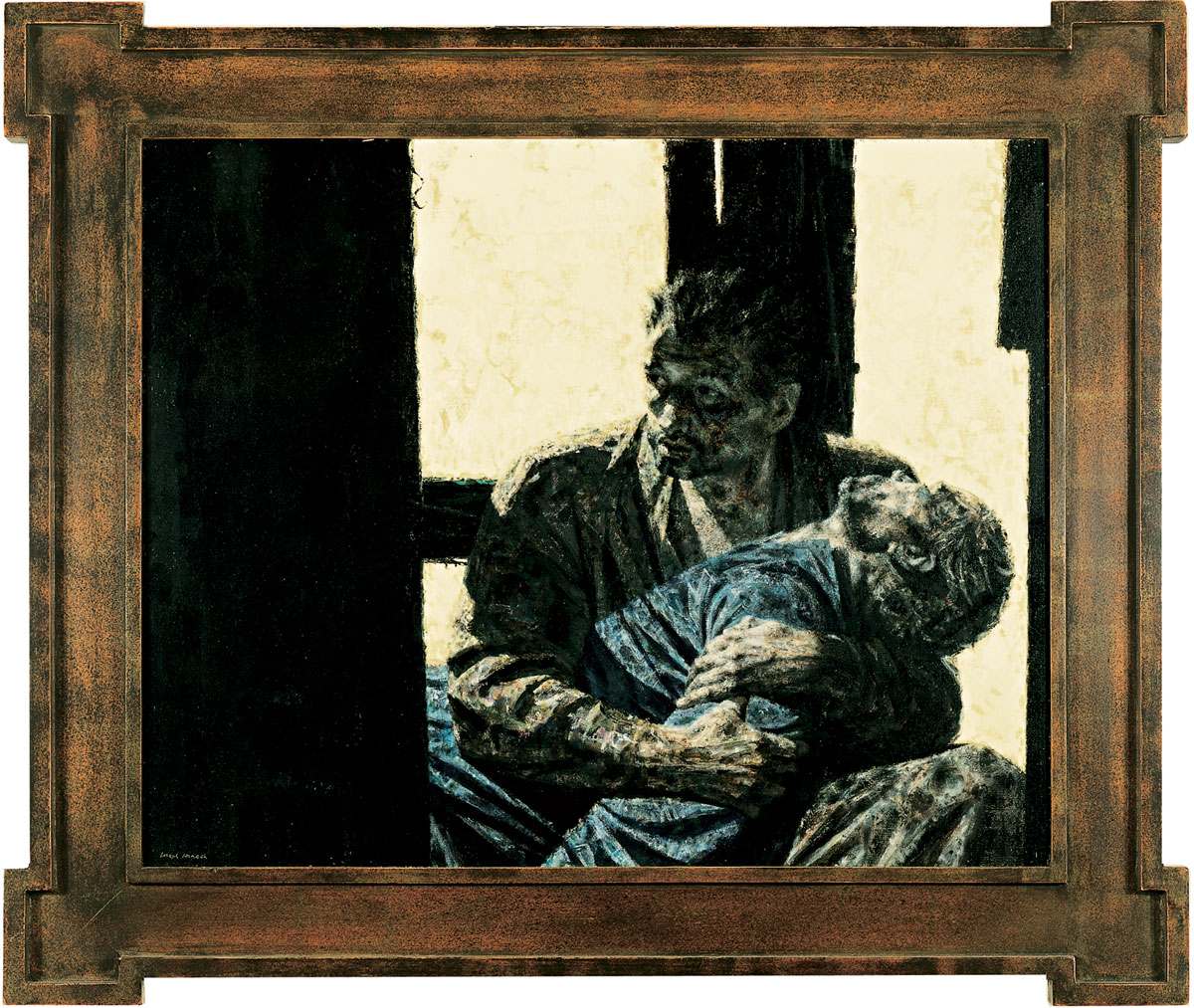

Courtesy of the Estate of Joseph Hirsch and Kennedy Galleries, New York. Photograph by R. H. Hensleigh.Deposition, 1967

Joseph Hirsch was born in Philadelphia and studied at the Philadelphia College of Art and with Henry Hensche in Provincetown and George Luks in New York. Luks was a member of The Eight, a group of painters at the beginning of the century who took ordinary people and everyday life as their subject. Their work, in turn, helped spawn the Ashcan School of urban realism and the Social Realism of the 1920s and 1930s that focused on the realities of American life, particularly during the Great Depression. Hirsch retained a lifelong focus on social commentary, once responding to a question about his art by saying, “I make cudgels”-evoking the social commitment of artists such as Raphael and Moses Soyer, Ben Shahn, Jack Levine, and Jacob Lawrence, all of whom were his friends.

Painted during the height of United States involvement in the Vietnam War, Deposition represents a modern pieta. Hirsch depicts a comrade in the role of the grieving Mary, holding the lifeless body of a soldier who seems paradigmatic of all young men sacrificed on the altar of war. The central image is rooted in the Social Realism of art before World War II, but is also connected to the existential doubt and implicit search for universal meaning in postwar Abstract Expressionism. This is conveyed in the Franz Kline-like painting produced as a backdrop to this scene of existential pondering of the human condition brought about by modern day militarism. The dense black and warm luminous spaces of the postwar modernist background allude to a twentieth-century form of crucifixion, in this context evoking the tension between obscurity and illumination, redemption and despair. Space is suggested by the layering of planes and the figures contained within, rather than through traditional perspective. The central figure stares obliquely into the unfathomable depths, as if contemplating the meaning of death and loss, sacrifice and heroism, the effects of nationalist ideologies, or the role of the individual on the larger stage of history. The scene is contained within a gilded frame that lends it an iconic status while the rust-like patination evokes a gritty industrial world.

During the 1930s, Hirsch was employed by the Works Progress Administration in Philadelphia where he completed murals for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Building and the Municipal Court. In 1941 he became affiliated with the Associated American Artists Gallery in New York, which also represented the well-known Regionalist artists Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton. During World War II, he worked for Abbott Laboratories, producing artworks to illustrate the war effort and served as a war artist recording events in the South Pacific, Italy and North Africa. After the war he continued his successful career, selling his paintings through New York galleries, working on commissions for corporations, and producing special projects, such as designs for playbills. During the 1960s and 1970s, Hirsch also produced paintings for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and was fascinated with the workman and his machinery, often using layered planes to compose his paintings. Barry Schwartz, in 1974, characterized Hirsch’s art as “a new humanism.”

Hirsch taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, the American Art School, University of Utah, and the Art Students League in New York until his death in 1981. His dramatic and socially observant works have won nearly every major award offered to American artists, but he was proudest of winning First Prize at the New York World’s Fair in 1939 for Whitey Being Told Like It Is, a painting of a black man sitting at a table with a white man, pounding his fist.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.