© Richard Anuszkiewicz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.

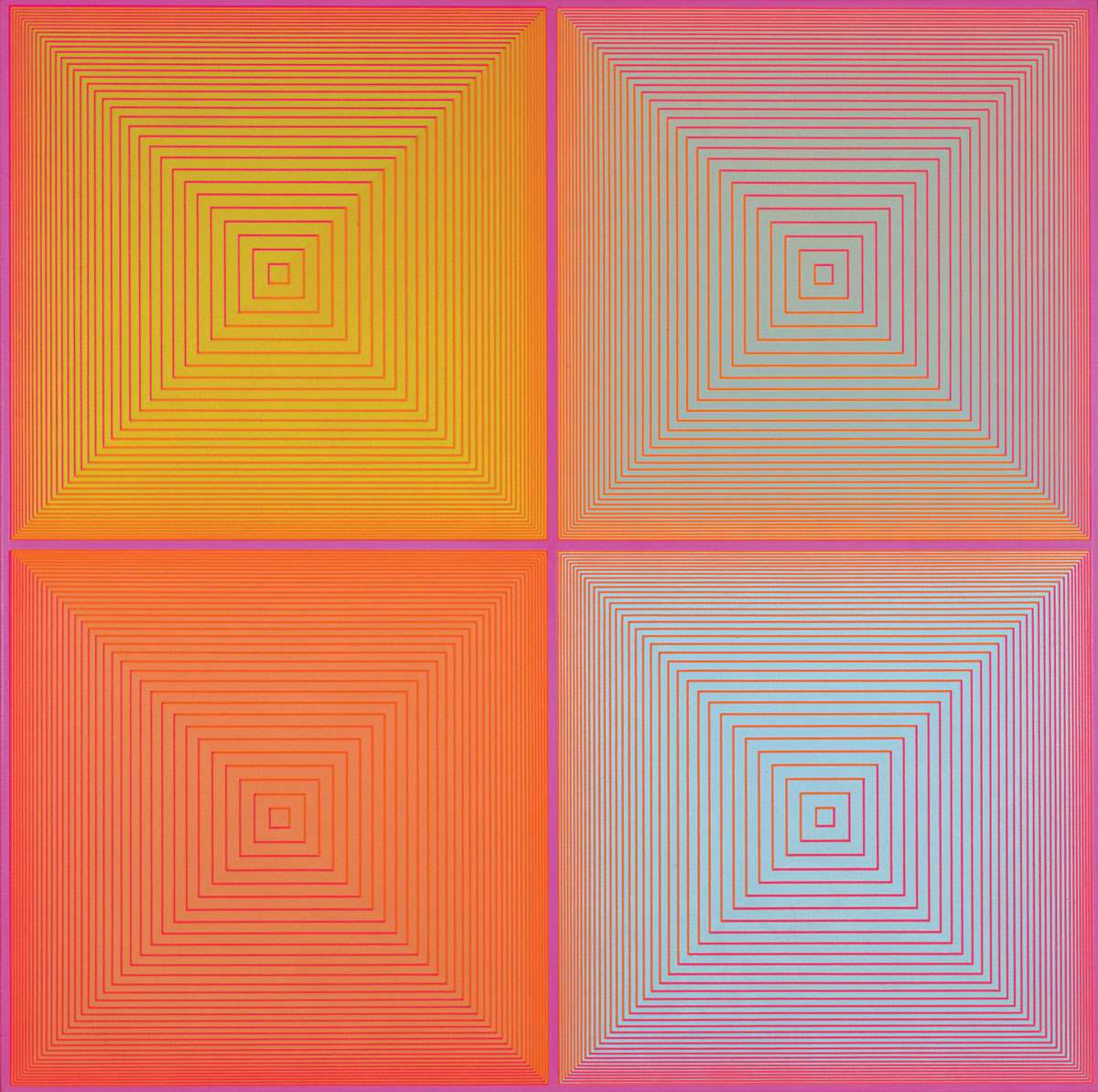

© Richard Anuszkiewicz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.Magenta Squared (271), 1969

Richard Anuszkiewicz came to critical notice in 1965, when he was included in the milestone exhibition that brought him international recognition-The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art. Anuszkiewicz was associated with a new type of abstraction known as Color Field Painting or Post-Painterly Abstraction, marked by an emphasis on large scale, unmodulated color, clean edge, and “all-over” design. The new painting addressed the expressive interactions of pure color and shape alone; it was devoid of all literary content and other outside references. Anuszkiewicz’s paintings were further linked to the sixties abstraction of Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, and Ellsworth Kelly. Known as Hard Edge Painting or Op Art, it cultivated clean-cut geometric form, saturated color, and an exceptional visual liveliness. Its essential character was an elaboration of an earlier tradition of abstraction that was developed at the Bauhaus in Germany and espoused by Josef Albers, with whom Anuszkiewicz had studied at Yale University.

Magenta Squared of 1969 is a vintage example of Anuszkiewicz’s contributions to modernist painting. With a squared dimension of three-feet, it was conceived by the artist, as were his other paintings at the time, as a form of collage produced with Liquitex, the brand name for a high viscosity, heavy body, water-based acrylic with a consistency similar to oil paint. Appearing on the market in 1963, Liquitex was a new medium with special properties Anuszkiewicz found appealing.

Typically, Anuszkiewicz first applied underpaintings of Liquitex paint to the canvas with a ground of magenta with a centered orange lozenge tangential to the framing edge. The geometric and straightedge striations of color that strive the eye in the painting are overlays of Liquitex strips that Anuszkiewicz adhered to the underpainted grounds. When Liquitex medium is added to acrylic, durable films of color can be made. Anuszkiewicz cut out his strips from such films. To create the quadrants for Magenta Squared, for example, he painted four Liquitex squares in mustard, light teal, light blue, and gray. With a penknife, he then cut out squared bands of varying widths in each of the colors, which he meticulously applied to the original canvas to give the impression of four concentric squares.

Anuszkiewicz chose Liquitex to facilitate an unusual form of collage painting. His textured surfaces also lend depth to color and help dematerialize literal surfaces into an appearance of pure, colored light. The reflected light emitted from his abstract shapes is iridescent and shimmering.

Through his color contrasts, each of which is calibrated to the same visual weight, the eye is made to dart while at the same time it is anchored by geometric shape. There is a contradiction of flatness and depth that the eye and mind cannot resolve, as evidenced in the flat color in the four squares of Magenta Squared that wrestles with the illusion of receding fractures into allegiance with each of the four squares. The diminishing widths of the color band in the painting creates a sense of wavering form. What fools the eye the most is what appears to be a shift of color. Each of the color strips in the four squares of Magenta Squared appears to change color. The shift is a function of the various underpaintings and the changes in perception they produce The gray bands of the lower-left square, for example, strike the eye as different in color as they cross over the underpainted orange lozenge and the magenta ground.

In expressive terms Anuszkiewicz sets order and disorder into a single system: geometry and logical progression are amalgamated with oscillating light and retinal confusions. We catch ourselves attempting to resolve these visual dissonances, but to no avail. That we cannot leads to the heart of the matter: Anuszkiewicz’s poetry of radiant indeterminacy.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.