© Philip Pearlstein. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.

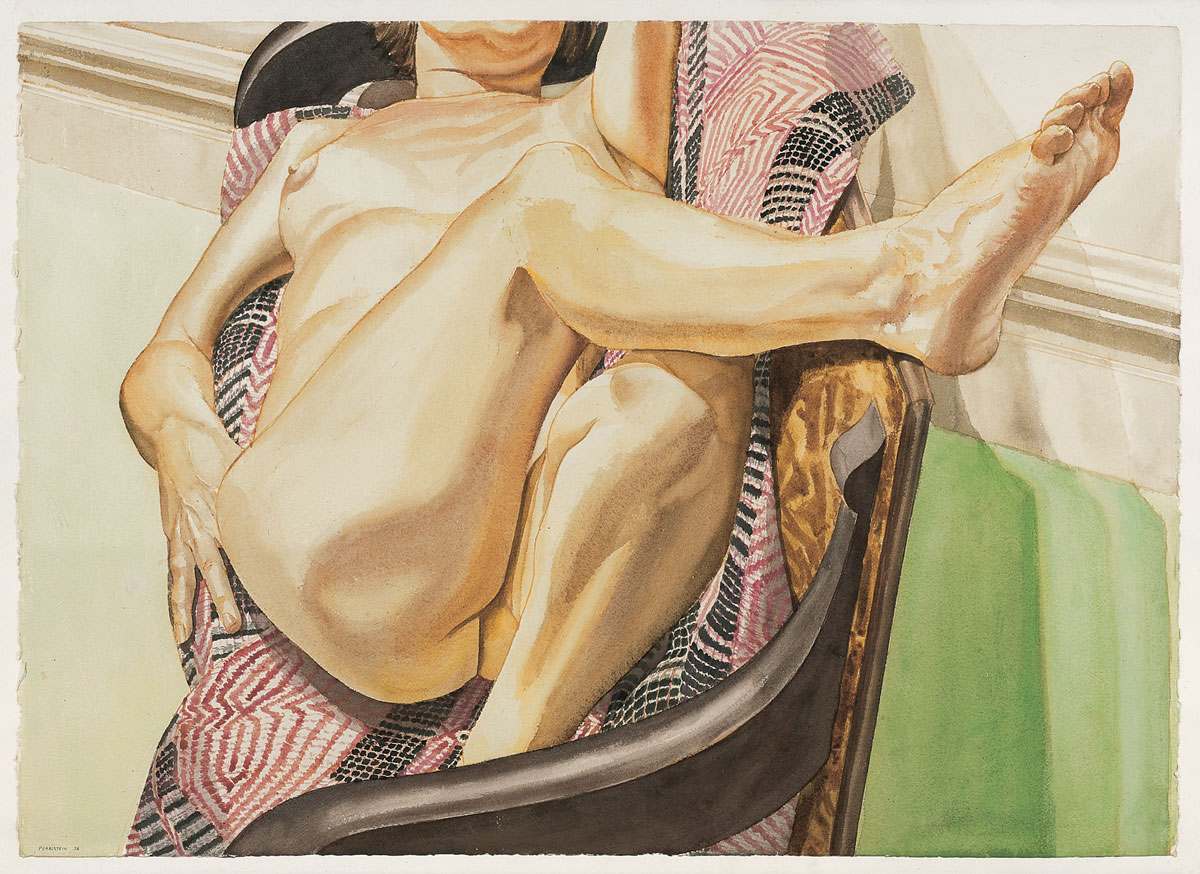

© Philip Pearlstein. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York. Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh.Female Model Reclining on Red and Black American Bedspread, 1976

Philip Pearlstein’s unsparing depictions of graceless nude models in stark studio settings have long set him apart from mainstream aesthetic currents and Female Model Reclining on Red and Black American Bedspread is a perfect representative example. Indeed, for only a few years at the beginning of his career in the 1950s did his then-expressionist paintings of landscapes coalesce with the artistic temper of the times. By 1961–62 Pearlstein had begun his momentous shift to the representation of the human figure and simultaneous abandonment of gestural, abstract painting. Eschewing excess emotionality in favor of clarity and directness, he claimed to want “nothing of mythology, or psychology to obtrude; I wanted to divest my vision of both Freud and Jung.”

Compositionally, however, Pearlstein was convinced that the realistic depiction of forms could rival the dynamics of abstract art. He explained, “The prime technical idea I took was that large forms deployed across the canvas produce axial movements that clash and define fields of energy forces, and that the realistic depiction of forms as they are in relation to one another in nature is as capable of creating these axial movements and fields of energy forces as are the forms of abstract art.”

Such forceful movements are clearly in play in Pearlstein’s large-scale watercolor in the Shuey Collection where the model’s upraised leg seems to thrust into the viewer’s space. Its pronounced movement to the right is countered by the outward bend of the model’s arm at left and the inclined baseboard that darts across the “back” of the composition. The model’s diagonal kick crosses the vertical established by the conjunction of her tucked-under leg and upraised arm at top center. All these crisscrossing axes are enclosed, moreover, within the fluid curves of the arms of the settee and the vibrating pattern of the red and black bedspread. For a medium often associated with soft, transparent effects, the forms in Pearlstein’s watercolor are as hard and specific as both the deadpan title and the painting’s dispassionate mood. As in most of Pearlstein’s figurative works, the head of the model is abruptly cropped, denying the viewer a sense of individuality or personality.

“There must be no soft edges in the painting and no soft sentimentality either,” Pearlstein asserted. Pearlstein’s bluntness about his intentions is understandable, given the artistic ethos in which his art was maturing. The Abstract Expressionism of Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock remained influential and the emergent Post-Painterly Abstraction of Helen Frankenthaler and Frank Stella was highly touted. Hence, Pearlstein’s shift to figuration struck many as too conservative for an artist well known in vanguard circles. Only in the late 1960s, with the advent of Photorealism represented by, among others, Chuck Close and Richard Estes- did Pearlstein’s point of view seem to be in synch with the zeitgeist. He, however, disassociated himself from the Photorealists by pointing out that he did not work from photographs. Indeed, a significant facet of Pearlstein’s reeducation was his turn to one of the hoariest traditions of western art: the nude model posed in a studio illuminated by artificial light.

Though traditional in this respect, one would never mistake a Pearlstein composition for one by Titian or Courbet. His cropped extremities, unidealized postures, and cool demeanor embody a late twentieth-century outlook marked by psychic distance rather than emotional engagement. Not surprisingly then, furniture and fabrics often share equal attention (an American bedspread, here, for instance) with the figure.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pearlstein studied at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon University) both before and after serving in World War II. Immediately after graduation in 1949 he moved to New York where he enrolled at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, completing his studies in 1955 and mounting his first one-person exhibition in the same year.

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.