Exhibition view. Photographer: PD Rearick.

In 1932, a remarkable educational experiment opened on the Cranbrook campus in the suburbs of Detroit, a new Academy of Art for advanced studies in the visual arts. Described by the New York Times as “part laboratory, part atelier, and part artist’s colony,” Cranbrook Academy of Art dedicated itself to the education of artists, architects, designers, and craftspeople. Rooted in the contemporary, its mission and vision was simple: to support the individual artist’s search for an expression unique and resonant to her time. Widely considered the cradle of mid-century design in America, the Academy quickly became a national and international leader, a reputation that holds true today as one of the top-ranked programs of its kind in the world.

Conceived as a radical experiment in the education of artists, Cranbrook Academy of Art rejected the academic and theoretical focus of arts education of the day and instead embraced individual creativity and expression through the actual making of work as a cornerstone of its philosophy. It encouraged the exploration of alternative materials, innovative processes, and new ideas across disciplines through both self-education as well as collaboration with peers. In this way, it was and remains a student-centric pedagogical environment.

The Academy not only pioneered a more organic and human-centric approach to modern design in America starting in the 1930s and helped shape the Studio Craft movement in America in the postwar period, but also radicalized the fields of architecture and design in the 1980s during the advent of postmodernism. Although many schools of radical art and design emerged in the twentieth century–places such as the Bauhaus or Black Mountain College–only Cranbrook Academy of Art remains today as a vital force in the worlds of art, architecture, craft, and design.

With Eyes Opened, surveys the history of the Academy since its official founding in 1932. With more than 250 works representing the various programs of study at the school–architecture, ceramics, design, fiber, metals, painting, photography, printmaking, and sculpture–the exhibition occupies all of the museum’s galleries. The largest such examination of the Academy since the landmark 1983 exhibition, Design in America, With Eyes Opened will be accompanied by a 600-plus page publication that chronicles the history of this storied institution and will feature 200 alumni representing the various programs of study, both historical figures and emerging voices, who have made remarkable contributions to the visual arts.

The exhibition is organized into a series of nine galleries that highlight the Academy’s contributions to the fields of art, architecture, craft, and design.

Florence Knoll would revolutionize modern office design for corporate America. Her friends at Cranbrook, such as Harry Bertoia and Eero Saarinen would introduce now-iconic furniture pieces for her company, Knoll International. This hotbed of talent would incubate a particularly American version of modern design, earning the Academy the moniker of the “cradle of mid-century modernism.”

These innovators would be followed by other designers such as Ruth Adler Schnee, Gere Kavanaugh, Clyde Burt, and John Risley, all of whom embraced wit and whimsy. The sculptural and expressive Brutalist furniture of artists such as Paul Evans continues through the contemporary designs of Chris Schanck and Jack Craig. Radical experiments in furniture, such as Urban Jupena’s fibrous lounge seating element, Ken Isaacs’ build-it-yourself Superchair, and an early pioneer of human-centered design and ergonomics—Niels Diffrient’s Humanscale each charted new design horizons.

Cranbrook dominated the genre of stacking chairs, with innovations by Don Albinson, whose clever design kept a stack of chairs in perfect alignment, David Rowland, who created a high-density stacker, and Hugh Acton, who designed the first ergonomic stacking armchair. Office task chairs were created by former Designer-in-Residence Michael McCoy, and alumni Niels Diffrient, and Charles and Ray Eames.

Cranbrook and the Chair celebrates artist-designed furniture, which has also been pioneered by the Academy through the work of Terence Main, Chris Schanck, Jonathan Muecke, Vivian Beer, Jack Craig, Jay Sae Jung Oh, and Evan Fay, among many others.

Although the age of the artists shown in this gallery is separated by nearly a half-century, there is shared energy that captures how artists can push boundaries and transcend disciplines in their search for the new.

As a complement to the figurative work of artists-in-residence Carl Milles and Zoltan Sepeshy, abstraction would enter the Academy through artists such as Harry Bertoia, and painting instructor Wallace Mitchell. Alumni such as José Joya, Frank Okada, and Wook-kyung Choi devoted their painting practices to abstraction. The canvas itself becomes a shaped figure in the work of artist-in-residence George Ortman, John Torreano, and artist-in-residence Beverly Fishman, whose pieces attain sculptural depth and symbolic meaning.

The materiality of painting is foregrounded in works by Jessica Dickinson, Rosalind Tallmadge, and James Benjamin Franklin, each of whom enhance painting’s tactile dimension through substances like plaster, epoxy, sand, sequin fabric, or carpet.

In the 1980s, Carl Toth used the photocopier machine as a camera, combining images through collage. Contemporary artists such as Sheida Soleimani and Chanel Von Habsburg-Lothringen use photomontage to explore themes of violence and gender, while the camera-less images of Brittany Nelson use antique photographic processes to create alternative imagescapes.

The scale and freedom of sculpture appealed to students in other departments as well, particularly the crafts. Large-scale fiber works by Olga de Amaral, Sonya Clark, and Nick Cave are complemented by the ceramics of Toshiko Takaezu and artist-in-residence Jun Kaneko. Even the practice of architecture at Cranbrook is akin to sculpture, as seen in the designs of Eero Saarinen and contemporary practitioners, such as Hani Rashid.

Although described by their respective materials, each discipline has exceeded such boundaries, as witnessed by ceramicists such as artist-in-residence Richard DeVore, Annabeth Rosen, and Marie Woo. In Metals, Myra Mimlitsch-Gray explores the social history of the material, while an artist such as Chunghi Choo has perfected the ability to sculpt her fluid forms in metal. Artists such as Joan Livingstone and Anne Wilson continue to push the boundaries of the field of fiber.

The desire to upend expectations can be seen in the “anti-jewelry” of J. Fred Woell or in the work of artist-in-residence Iris Eichenberg; the radical basket weaving of Lillian Elliott and her mentor Ed Rossbach; or the creation of the field of studio glass by Harvey Littleton, who had studied Ceramics. Even in the design fields, the influence of crafts can be found in the experimental use of materials and techniques and the beauty of handcrafted product design models made before the era of 3D printing and computer modeling.

Cranbrook artists continue to re-conceptualize the portrait through painting, sculpture, and photography, reinventing the traditional genre through a contemporary lens.

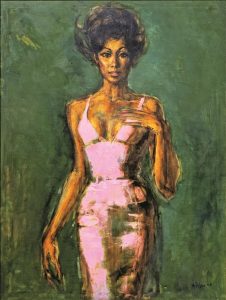

Work by Zoltan Sepeshy and Artis Lane shows each one’s approach of capturing the sitter’s essence through a figural likeness. Painter Charles Pachter has collaborated with his friend author Margret Atwood, capturing her spirit on canvas. Marianna Olague, Jova Lynne, and Conrad Egyir explore the social and political underpinnings of portraiture while reclaiming space for their subjects.

Corine Vermeulen and Liz Cohen use the documentary style of photography, but add their contemporary interpretations to transform the work into narratives of their subjects while Shanna Merola and Ricky Weaver employ the techniques of collage and doubling respectively to disrupt distinct identities. Shiva Ahmadi infuses the Persian tradition of miniature painting with social critique while Sarah Catherine Blanchette subverts familiar forms in favor of fragmentation and re-materialization, turning photos into luxurious fiber.

This gallery extends the collection beyond the museum walls, showcasing sketches for many of the naturally-inspired works found on Cranbrook’s campus, from the Milles’ sketches for both Europa and the Bull and Running Dogs to small decorative elements such as Fredericks’ water spigots which take the shape of a Japanese goldfish, lizard, and frog.

The reputation of the Academy’s influential graphic design program grew tremendously through its use of the medium from the 1970s through the 1990s under the tenure of designer-in-residence Katherine McCoy. The use of collage and photomontage techniques that layered provocative photography and illustration with progressive typography, decades before the desktop computer, can be seen in the promotional posters for Academy programs created by her and students of the design program in the 1970s and 1980s.

More oblique statements and personal messages dominated the poster work from designers in the 1980s and 1990s, and this tradition of experimental design continues with designer-in-residence Elliott Earls, whose prints, installations, and video work routinely crosses media and transcends disciplinary expectations.

Jim Miller-Melberg, who studied sculpture, supplied cast concrete playground features to parks around the country for decades through his company, Form. Millions of children have likely played on his iconic, mid-century designs that included abstract forms along with signature animals, such as his turtles, porpoises, and camels.

Cranbrook Art Museum is grateful to the following for their generous support of the exhibition and publication:

Major Sponsors

Sculpture Court Sponsor

Major Gallery Sponsors

Gallery and Artist Sponsors

In-Kind Sponsors

(as of May 7, 2021)

Copyright © 2026 Cranbrook Art Museum. All rights reserved. Created by Media Genesis.